John S. McCain Sr.

John S. McCain Sr. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s) | Slew |

| Born | 9 August 1884 Carroll County, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Died | 6 September 1945 (aged 61) Coronado, California, U.S. |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1906–1945 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | |

| Battles / wars | |

| Awards | |

| Spouse(s) | Katherine Davey Vaulx |

| Children | 3 |

| Relations |

|

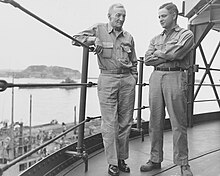

John Sidney "Slew" McCain Sr. (9 August 1884 – 6 September 1945) was a United States Navy admiral and the patriarch of the McCain military family. McCain held several commands during the Pacific War of World War II and was a pioneer of aircraft carrier operations. He and his son, John S. McCain Jr., were the first father-and-son pair to achieve four-star admiral rank in the U.S. Navy.

A graduate of the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland, class of 1906, McCain's early career was on battleships and cruisers. During World War I, he served on convoy duty in the Atlantic. From 1918 to 1935, he alternated between duty ashore with the Bureau of Navigation, where he developed officer personnel policies, and at sea, where he commanded the cargo ship USS Sirius and ammunition ship USS Nitro. He attended the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1928 and 1929. In 1935, he qualified as a naval aviator, and commanded the aircraft carrier USS Ranger from 1937 to 1939.

During World War II, McCain commanded land-based air operations in support of the Guadalcanal campaign. He served as Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics and Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Air. In 1944–1945, he led Task Force 38 in operations off the Philippines and Okinawa and air strikes against Formosa and the Japanese home islands that caused the destruction of Japanese naval and air forces in the closing period of the war. McCain died four days after attending the formal Japanese surrender ceremony on 2 September 1945.

Early life, education, and family

[edit]John Sidney "Slew" McCain was born in Carroll County, Mississippi, on 9 August 1884, the third child and second son and namesake of plantation owner John Sidney McCain and his wife Elizabeth-Ann Young. He had an older brother, William Alexander, an older sister, Katherine Louise, and three younger siblings: Mary James, Harry Hart and Joseph Pinckney.[1][2][3]

McCain attended the University of Mississippi for the 1901–1902 academic year, where he joined the Phi Delta Theta Fraternity, and then decided to attend the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, where his brother William Alexander was enrolled. To practice for its entrance exams, he decided to take the ones for the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland; when he passed and earned an appointment from Senator Anselm J. McLaurin, he decided to attend there instead.[4][5][6]

On 25 September 1902, McCain entered the Naval Academy. He acquired the nickname "Slew". Each summer, midshipmen went on a training cruise to familiarize them with shipboard life. The 1903 cruise was on the USS Chesapeake, a barque skippered by Commander William F. Halsey Sr., whose son William F. Halsey Jr., a midshipman two years ahead of McCain, was also aboard. McCain then went to New York for Independence Day celebrations on the battleship USS Indiana, and returned to Annapolis on the sloop-of-war USS Hartford. The 1904 cruise was also on the Hartford, with a return trip on the battleship USS Massachusetts, and the 1905 cruise on the monitors USS Florida and Terror. McCain failed his annual physical in 1905 on account of defective hearing, but the condition was waived due to the great need for officers.[4][7]

McCain's academic performance was lackluster: when he graduated on 12 February 1906, he ranked 79th out of 116 in his class, and the yearbook labeled him "The skeleton in the family closet of 1906."[8][9] His classmates included William L. Calhoun, Aubrey W. Fitch, Frank J. Fletcher, Robert L. Ghormley, Isaac C. Kidd, Leigh Noyes, John H. Towers and Russell Willson.[8]

Early career and World War I

[edit]Midshipmen were not immediately commissioned, but had to first serve a year or two at sea. McCain's first assignment, in April 1906, was the battleship USS Ohio, the flagship of the Asiatic Fleet, based at Manila Bay. After five months he was transferred to the protected cruiser USS Baltimore. Then, in January 1907, he became the executive officer of the patrol boat USS Panay, under the command of Ensign Chester W. Nimitz. In July, he became the engineering officer on the destroyer USS Chauncey. He was promoted to ensign on 18 March 1908.[10] On 27 November 1908, he joined the battleship USS Connecticut for the home stretch of the Great White Fleet's world cruise from 1907 to 1909. The Connecticut sailed through the Suez Canal and participated in disaster relief efforts for the 1908 Messina earthquake in Sicily before reaching Hampton Roads on 22 February 1909. He was then ordered to report to the armored cruiser USS Pennsylvania on the West Coast.[11][12]

McCain married Katherine Davey Vaulx, who was eight years his senior, in Colorado Springs, Colorado, on 9 August 1909, in a ceremony performed by Vaulx's clergyman father, James Junius Vaulx. The couple had three children: John Sidney McCain Jr., James Gordon McCain, and Catherine Vaulx McCain.[13] In December 1909, McCain joined the crew of the armored cruiser USS Washington as its engineering officer. He appeared before the examination board for promotion to the rank of lieutenant (junior grade) on 2 February 1911, and was questioned about his knowledge of seamanship, navigation, gunnery and engineering. He was promoted on 10 March, with seniority backdated to 13 February 1911.[12][13]

Duty afloat alternated with duty ashore, so McCain's next posting was to the Charleston Navy Yard, where he was in charge of the machinist's mates school. While there, he was promoted to lieutenant on 5 August 1912, backdated to 1 July, and he temporarily commanded the torpedo boat USS Stockton during a naval review in New York from 13 to 15 October 1912.[14][15] In April 1914, he became the executive officer and engineering officer of the armored cruiser USS Colorado, the flagship for the Pacific Fleet. During 1914 and 1915, it patroled the Pacific coast of Mexico during the Mexican Revolution. On 11 September 1915, he joined the armored cruiser USS San Diego as its engineering officer. The ship was placed in reserve in February 1917, but was restored to active service after the American entry into World War I in April. He assumed the acting rank of lieutenant commander on 31 August. This became substantive on 16 January 1918, with seniority backdated to 22 September 1917.[11][16][15]

McCain and the San Diego served on convoy duty in the Atlantic Ocean,[11] escorting shipping through the first dangerous leg of their passages to Europe. Based out of Tompkinsville, New York, and Halifax, Nova Scotia, San Diego operated in the weather-torn, submarine-infested North Atlantic. McCain left San Diego on 26 May 1918, two months before she was sunk on 19 July by a mine laid by a U-boat, for a new assignment in the Bureau of Navigation in Washington, D.C., dealing with the assignment of naval personnel, with the rank of commander.[11][16][17]

Interwar period

[edit]Battleships and the Bureau of Navigation

[edit]The Bureau of Navigation handled the assignment, classification and promotion of naval personnel. McCain had to deal with both the wartime expansion of the Navy to 31,194 officers and 495,662 men in 1918, and its post-war demobilization that reduced the Navy to 10,109 officers and 108,950 enlisted personnel in 1920. The Bureau of Navigation sought to retain personnel with valuable skills in the regular service where possible. He served on a board that drafted regulations and legislation for such transfers, and published an article in the US Naval Institute Proceedings on the wartime "hump" of officers and the system of promotion based on seniority.[18][19] In addition to professional articles in the Proceedings, during the inter-war years, McCain was a would-be author who wrote fiction that was never published, including some adventure stories under the name Casper Clubfoot. In one story, The Rout of the Red Mayor, the heroes of the story were the Ku Klux Klan.[20][21]

McCain joined the newly-commissioned battleship USS Maryland as its navigator while it was still fitting out at Newport News Shipbuilding in June 1921. He returned to the Bureau of Navigation in April 1923, working in the office of officer personnel, whose director was Captain William D. Leahy. McCain participated in another board, drafting legislation of an Equalization Bill that sought to provide officers in specialist staff corps with the same promotion opportunities as line officers.[22][23] The bill was eventually signed into law on 10 June 1926. He also convinced the General Board of the merits of raising the number of years of service for captains before mandatory retirement by a year.[24][25]

On 6 October 1925, McCain was called before a board of inquiry headed by businessman Dwight Morrow into the crash of the airship USS Shenandoah. McCain was asked whether aviators should be a separate corps. McCain supported the position of the Bureau of Navigation and Bureau of Aeronautics that aviators should remain line officers, and therefore eligible to command ships, but he acknowledged that they had to forgo flight pay during service at sea in non-aviation positions.[24] McCain returned to sea duty in April 1926 to assume command of the cargo ship USS Sirius. In August he became the executive officer of the battleship USS New Mexico, which was commanded by Leahy.[26] McCain submitted a request for flight training in January 1928, but although he passed the physical examination, he was rejected because he exceeded the Bureau of Navigation's age limits for aviator training.[27]

In February 1928, McCain entered the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. His 47 classmates included future admirals H. Kent Hewitt, Alan G. Kirk and Jesse B. Oldendorf. Students studied the works of Alfred Thayer Mahan, Julian Corbett and Herbert Richmond, with an emphasis on major naval actions like the Battle of Trafalgar, Battle of Tsushima and the Battle of Jutland. McCain wrote theses on the "Causes of the Spanish American War, and the Naval and Combined Operations in the Atlantic, Including the Transfer of the Oregon" and "Foreign Policies of the United States".[26][28][29] On graduation in June 1929, he returned to the Bureau of Navigation, before assuming command of the ammunition ship USS Nitro on 9 June 1931. He was promoted to the temporary rank of captain on 25 September. This became substantive in June 1932, and with seniority backdated to 30 June 1931.[26][30] He left Nitro on 1 April 1933 and returned to the Bureau of Navigation for his third and final tour of duty there. This time he worked on legislation to provide sailors for new ships authorized under the 1934 Vinson-Trammell Act.[26]

Naval aviation

[edit]The Vinson-Trammell Act opened up another opportunity for flight training. Only naval aviators and observers could command aircraft carriers, aviation shore establishments or air units, but the expansion of the fleet authorized by the act created a shortage of aviators qualified for senior command positions. Leahy was now Chief of the Bureau of Navigation, and he waived the age requirement. McCain's request also received the endorsement of the Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, Rear Admiral Ernest J. King, who had completed flight training in 1927. McCain passed the physical; he now required a full set of dentures but otherwise was considered fully fit and teeth were not a requirement.[27]

On 20 June 1935, McCain reported to Naval Air Station Pensacola for flight training. Training was conducted on the old Consolidated NY-1 and the new Stearman NS-1 biplanes. The training consisted of 465 hours of classroom instruction in aerial navigation, aerodynamics, aerology, aircraft engines, aerial gunnery and communications, and 282.75 hours of flight time that included some night flying.[31][32]

On 18 April 1936, McCain was detached from flight training and went to Naval Air Station North Island in San Diego, where he reported to the aircraft carrier USS Lexington, which was commanded by Annapolis classmate Captain Aubrey Fitch. Over the following weeks McCain was an observer of war games that simulated an attack on the Panama Canal. At the conclusion, he returned to San Diego on the aircraft carrier USS Ranger, and then resumed his aviation training at Pensacola.[31][32]

McCain took his first solo flight on 26 July and, on 24 August, at the age of 52, was awarded his wings and became Naval Aviator No. 4280. He was the second-oldest aviator to earn his wings at Pensacola, after William F. Halsey Jr., who had graduated the year before. His flight training continued until 10 September, by which time he had completed 325 flights totaling nearly 289 hours.[31][32]

McCain hoped for command of an aircraft carrier, but his first aviation posting was to Coco Solo in the Panama Canal Zone. Exercises were conducted under King's watchful eye.[33][34] On 7 April 1937, McCain received orders to assume command of the Ranger. He joined the ship in San Francisco on 1 June, and four days later hoisted his flag, relieving Captain Patrick N. L. Bellinger. Bellinger's executive officer, Commander Alfred E. Montgomery, stayed on as his executive officer. The embarked air group consisted of four squadrons: VF-4, equipped with Grumman F3F fighters; VB-4, with Great Lakes BG dive bombers; and VS-41 and VS-42, with Vought SBU Corsair scout-bombers.[35][36]

In September, the Ranger made a goodwill tour to Peru, where McCain was awarded the Order of the Sun of Peru and the Peruvian Aviation Cross. After an overhaul at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard from 27 October 1937 to 28 January 1938, the Ranger participated in Fleet Problem XIX in April and May 1938, which simulated an attack on Hawaii, and Fleet Problem XX in the Caribbean in February 1939, again overseen by King, who flew his flag on the Ranger in the final stages of the exercise.[35][36] Based on his experience in command, McCain became an advocate of the armoured flight deck, which no American carrier possessed at that time.[37][38]

On 1 July 1939, McCain assumed command of Naval Air Station North Island, the only one of its kind on the West Coast until Naval Air Station Alameda became operational on 1 November 1940. McCain helped Alameda become established, providing assistance in the form of personnel, equipment and expertise.[39][40] He became eligible for promotion to rear admiral in 1939, but was passed over. He felt that his work on legislation for the Bureau of Navigation had not received the recognition that it deserved, and took steps to correct the record. He enlisted the support of King and retired Rear Admiral Richard H. Leigh. His promotion was approved by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on 23 January 1941.[41][42]

Upon his promotion, McCain assumed command of Aircraft, Scouting Force. In this role he was responsible for the land-based aircraft, and was concurrently Commander, Patrol Wings, United States Fleet. He was impressed with the capabilities of the Consolidated PBY Catalina, but was aware of its limitations. While he advocated an offensive role for the aircraft, he knew that they were too vulnerable to attack shipping in daylight. He therefore prodded the Bureau of Ordnance to modify the Mark 13 torpedo so that it could be released from an altitude of 200 to 300 feet (61 to 91 m), thereby reducing the risk of aircraft crashing into the sea at night.[43][44] Even after modification, the torpedoes were plagued with reliability problems that were not resolved until 1944. By then, a series of changes had been made that allowed the torpedoes to be dropped from 800 feet (240 m) at a speed of 260 knots (480 km/h; 300 mph), which greatly enhanced the chance of the torpedo bomber surviving the attack.[45]

World War II

[edit]The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 brought the United States into World War II. Of the 54 patrol planes based there, only one was undamaged. McCain deployed his patrol planes to warn against attacks by Japanese submarines or aircraft carriers or an invasion of Hawaii or California. His command was redesignated Patrol Wings, Pacific Fleet, on 10 April, and was transferred from the control of the Western Sea Frontier to Admiral Chester W. Nimitz's Pacific Fleet.[46]

Guadalcanal campaign

[edit]On 1 May 1942, McCain was appointed Commander, Aircraft, South Pacific Area. As such, he commanded land-based Allied air operations supporting the Guadalcanal campaign in the Solomon Islands.[47] He hoisted his flag on the seaplane tender USS Tangier in Noumea on 20 May; it was replaced by the USS Curtiss in June. His immediate task was developing air bases to support his patrol planes and heavy bombers.[48] Aircraft carriers were available for the landings on Tulagi and Guadalcanal on 7 August, but only for the first two days. McCain's aircraft then had to provide air support until the airfield on Guadalcanal could be made operational. However, his fighters based on Efate did not have the range to reach Guadalcanal without drop tanks, which were in short supply.[49] He gave a high priority to completion of a new airfield on Espiritu Santo.[50] A fighter squadron arrived on 28 July and first Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress landed on the newly-completed airfield the next day.[51]

In the Battle of Savo Island on 8 August, a Japanese cruiser force attacked the Allied one screening the landing, sinking one Australian and three American cruisers, while suffering only light damage in return. It was the Navy's second greatest defeat, exceeded only by Pearl Harbor. Admiral Arthur J. Hepburn, a former commander in chief, United States Fleet, and the chairman of the General Board, conducted an investigation into the circumstances.[52] In his report, Hepburn noted that there was a twilight zone between "culpable inefficiency on the one hand and more or less excusable error of judgment on the other".[53] He ascribed the defeat to the Allied force being surprised. While not specifically blaming McCain, Hepburn attributed this to the failure of air patrols to detect the approach of the Japanese force. In his endorsement of Hepburn's report, Nimitz concurred that one of the causes of the disaster was the "failure of either carrier or land-based air to conduct effective search and lack of coordination of searches."[53]

In the aftermath of the disaster, the commander of the South Pacific Area, Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley, ordered McCain to withdraw the seaplane tenders USS Mackinac and McFarland from Malaita and Ndeni respectively, which he regarded as now too vulnerable. This disrupted the search plan and forced McCain to deploy his PBY patrol planes from Espiritu Santo and a new base McCain established at Vanikoro in the Santa Cruz Islands. The airfield on Guadalcanal, which the 1st Marine Division's commander, Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift, named Henderson Field after Major Lofton R. Henderson, a marine aviator who had been killed in the Battle of Midway, was considered operational on 12 August. The following day, the escort carrier USS Long Island arrived at Suva with 18 F4F Wildcat fighters and 12 SBD Dauntless dive bombers. The ship's captain asserted that the marine fighter pilots were not sufficiently trained to take off from the carrier, so McCain swapped eight of them with more experienced aviators from Efate. They arrived on Guadalcanal on 20 August, and became the nucleus of what became the Cactus Air Force.[54][55]

McCain seized every opportunity to reinforce the Cactus Air Force. He sent Army Bell P-400 Airacobra fighters, and retained 11 SBDs from the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise that landed on Henderson Field after the Enterprise was damaged in the Battle of the Eastern Solomons.[56] But aircraft were lost at alarming rates.[57] Nimitz was not satisfied with McCain's performance and resolved to relieve him of his command.[58] Meanwhile, in Washington, DC, Admiral Ernest J. King, who was now the Commander in Chief US Fleet, had clashed with the chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, Rear Admiral John H. Towers, over King's plans to reorganise the Navy Department, which involved asserting more control over the bureaus. King and Nimitz met in San Francisco on 6 and 7 September 1942, and agreed on new command arrangements: Towers would be promoted to vice admiral and sent to Nimitz as Commander Naval Air Force, Pacific Fleet; the incumbent, Rear Admiral Aubrey W. Fitch, would replace McCain as Commander, Aircraft, South Pacific Area; and McCain would succeed Towers as chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics.[59][60] McCain was awarded the Navy Distinguished Service Medal for his part in "the occupation of the Guadalcanal-Tulagi area by our forces and the destruction and serious damaging of numerous aircraft and vessels of the enemy".[41]

Bureau of Aeronautics

[edit]

Fitch relieved McCain on 21 September.[61] Time magazine opined that "it was a promotion for Admiral Towers but a demotion for the Navy's air arm ... New BuAer Chief Rear Admiral John Sidney McCain, 58, is a good officer. But like many other so-called air admirals, he got an airman's rating late, is not an airman by profession, but a battleship admiral with pay-and-a-half and a flying suit."[62] His son Gordon wrote a rebuttal letter to Time, pointing out that while McCain "has had no armchair or laboratory contact with 'air developments' he has had considerable peacetime and some combat flying experience."[63] In a letter to Nimitz, the Secretary of the Navy, Frank Knox, also defended the appointment. "Towers," he wrote, "while able, is not a good administrator or coordinator. I think McCain is both."[64]

McCain inherited from Towers an organization still in the throes of a massive wartime expansion. There were 1,098 officers on duty in the Bureau of Aeronautics in December 1942, up from 58 three years before. His first priority was to meet the needs for aircraft in the South Pacific, where they were being shot down and written off faster than they could be delivered. The Navy had 2,172 aircraft in June 1940; by the end of 1942 it had 7,058. The War Production Board had set a target of 107,000 aircraft to be delivered in 1943, of which the Navy was to receive 24,116. The Bureau of Aeronautics estimated that only 17,000 would be delivered, but that was still twice as many as had been delivered in 1942.[65][66]

On 13 December 1942, Knox issued a directive that authorized the technical bureaus "to negotiate, prepare, and execute their own contracts."[67] Henceforth, the Bureau of Aeronautics procured major aeronautical items like air frames and engines.[67] To administer procurement, McCain created Contracts, Contracts Administration, and Records and Distribution sections within the Procurement Branch of Bureau of Aeronautics's Material Division.[68] Training the required personnel was another challenge. On 8 April 1943, the Bureau of Aeronautics estimated that 35,495 pilots would be needed in 1943 but only 30,500 would be available.[69]

An important aspect of the Bureau of Aeronautics's work was the development of requirements for new aircraft in response to lessons learned in combat.[69] Like many personnel who had served on Guadalcanal, McCain's sleep had been interrupted by Washing Machine Charlie, Japanese aircraft that had conducted nocturnal operations over the island. In June 1943, Marine aviators returning to the UK reported that the British believed that a twin-engine night fighter was required. The result was the development of the Grumman F7F Tigercat. As an interim measure, the Bureau of Aeronautics fitted Vought F4U Corsair and Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters as night fighters. McCain also believed that these fighters could serve as bombers and had them modified to carry bombs and rockets. He also took steps to develop jet aircraft, starting with the Ryan FR Fireball.[70][71]

In May 1943, King made another attempt to reorganize the Navy Department to bring more of it under his own control. He proposed to do so by creating four Deputy Chiefs of Naval Operations. This did not meet with approval from Roosevelt, but the creation of a Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Air was authorized. McCain was chosen for the position, with the rank of vice admiral from 28 July. The Bureau of Aeronautics's Planning, Personnel, Training, and Flight Divisions were transferred to the new office. Rear Admiral DeWitt Clinton Ramsey succeeded McCain as Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics.[72][73]

Marianas and Philippines

[edit]

By March 1944, McCain was aware that he was in line to command an aircraft carrier task force. He approached Commander John S. Thach and asked him to become his operations officer. Thach accepted, and McCain arranged for both to be attached to the Fifth Fleet on temporary duty. From 26 May to 21 June, McCain was on board the cruiser USS Indianapolis, the flagship of the fleet commander, Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, whence he was able to observe the invasion of Saipan and the Battle of the Philippine Sea. At this stage of the war, the fleet was divided into task forces, which in turn were divided into two to five task groups. Each aircraft carrier task group consisted of four or five aircraft carriers, along with their destroyer, cruiser and battleship escorts.[74][75]

Next, McCain transferred to the aircraft carrier USS Lexington, where he understudied Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher, the commander of the First Fast Carrier Task Force Pacific, also known as Task Force 58, while Thach worked with Mitscher's operations officer, Captain Arleigh Burke. Finally, from 24 to 26 June, McCain was an observer with Rear Admiral John W. Reeves Jr.'s Task Group 58.3. After Task Force 58 returned to Eniwetok, McCain flew to the United States on 3 July and was back in Washington, DC, three days later. He handed over the position of the Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Air to Fitch on 1 August.[74][75]

Instead of McCain taking charge of the First Fast Carrier Task Force Pacific as he expected, Mitscher stayed on, and McCain was nominally given command of the Second Fast Carrier Task Force Pacific.[76][77] Under a new organization implemented by Nimitz, there would be two fleets. They would consist of the same ships, but there would be two fleet commanders, Halsey and Spruance. When Halsey was in charge, the fleet would be called the Third Fleet; when Spruance was in charge, it would be called the Fifth Fleet. While one commanded at sea, the other would plan the next operation.[78]

McCain would have liked to have taken Mitscher's experienced staff, but under this dual-command arrangement he was compelled to select a new one. For his chief of staff, he chose Rear Admiral Wilder D. Baker. As a learning exercise, McCain took over Task Group 58.1 from Rear Admiral Joseph J. Clark. This was awkward, as McCain was senior to Mitscher. Task Group 58.1 comprised the aircraft carriers USS Wasp and Hornet, the light carriers USS Cowpens and Belleau Wood, the cruisers USS Boston Canberra and Wichita, and eleven destroyers. McCain hoisted his flag on the Wasp on 18 August. Clark remained on board to advise McCain until the end of September. When Admiral William F. Halsey Jr. assumed command of the fleet from Spruance on 26 August, the fleet became the Third Fleet and Task Group 58.1 became Task Group 38.1.[76][77]

Task Group 38.1 sortied from Eniwetok on 29 August 1944. McCain conducted a series of air strikes on targets in the Caroline Islands and Philippines in support of the landings on Peleliu and Morotai. In his report on the operations, McCain recommended that the number of fighters aboard his Essex-class aircraft carriers be increased, as in the future they would be often operating in range of large numbers of land-based aircraft. King authorized an increase in their fighter strength from 36 to 54, with a corresponding reduction in the number of Curtiss SB2C Helldiver dive bombers being carried.[79][80]

After revictualing at Manus Island, Task Group 38.1 sortied again on 2 October, this time in support of the landing on Leyte. McCain conducted a series of strikes against airfields on Formosa, which precipitated the Formosa Air Battle. On the night of 12 October, Task Group 38.1 was attacked by fourteen Japanese aircraft, all of which were shot down by anti-aircraft guns and night fighters. At 18:23 on the following evening, there was another attack by ten torpedo bombers that were not picked up on radar. Canberra was torpedoed and Wasp suffered minor damage when one of the bombers crashed off the starboard bow. McCain had Wichita take Canberra in tow, and had his carriers provide protective air cover. The Japanese attacked again at dusk the next evening, and torpedoed the USS Houston, which had been sent to augment McCain's screen. On 15 October, Task Group 38.1 came under relentless attack by an estimated 80 aircraft, of which 52 were claimed to have been shot down. Two American fighters were lost, but the cruisers were saved.[81][82]

McCain was awarded the Navy Cross. His citation read:

The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to John Sidney McCain, Vice Admiral, U.S. Navy, for extraordinary heroism and distinguished service in the line of his profession as Commander, Task Group 38.1, after the torpedoing of the USS Canberra and USS Houston by Japanese aerial forces, ninety miles off the Island of Formosa, during the period 13 to 15 October 1944. Vice Admiral McCain interposed his task group to cover the withdrawal of the USS Canberra and USS Houston and by his skillful and courageous handling of his forces broke up repeated heavy enemy air attacks. His actions contributed in great measure to the ultimate successful salvaging of the two damaged cruisers. Vice Admiral McCain's inspiring leadership and the valiant devotion to duty of his command contributed in large measure to the outstanding success of these vital missions and reflect great credit upon the United States Naval Service.[83]

Battle of Leyte Gulf

[edit]

After replacing the damaged ships, Task Group 38.1 consisted of the carriers USS Wasp, Hornet and Monterey; cruisers USS Chester, Pensacola, Salt Lake City, Oakland and San Diego; and twelve destroyers. On 22 October they were augmented by the return of Cowpens and the addition of the USS Hancock and its escorts. That night, Halsey directed McCain to replenish at Ulithi, so Task Group 38.1 headed east.[84][85] At 08:46 on 24 October, with indications of an impending naval battle, Halsey ordered McCain to reverse course, refuel at sea, and conduct air searches. McCain reached the rendezvous point and refueling commenced at 07:24 on 25 October. Monitoring the radio circuits, McCain realised that Vice Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaids' escort carriers were under attack off Samar and, on his own initiative, ordered Task Group 38.1 to complete refueling and head towards Samar at 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph).[86][87]

McCain recovered his combat air patrol and increased speed to 30 knots (56 km/h; 35 mph). Although the airfield at Tacloban on Leyte reported that it was usable in an emergency, McCain ordered his Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo planes loaded with bombs instead of torpedoes to extend their range. To save time, since the wind was from the east, he adopted the unusual maneuver of having the carriers increase speed to 33 knots (61 km/h; 38 mph), turn into the wind to launch aircraft, then turn about and catch up with the escorts. His first strike, consisting of 48 Hellcats, 33 Helldivers and 19 Avengers departed at 11:02, followed by a second of 35 Hellcats, 20 Helldivers and 21 Avengers. Six aircraft were lost; several had to land at Tacloban or on the escort carriers. A single bomb hit was made on the Japanese cruiser Tone. While King, Nimitz and subsequent historians had considerable criticisms of Halsey's handling of the Third Fleet in the battle, McCain was commended for his handling of Task Group 38.1, especially for actions taken on his own initiative.[86][88]

Task Force 38 commander

[edit]On 30 October 1944, McCain assumed command of Task Force 38.[89] McCain conducted air strikes against targets in the central Philippines and Luzon while covering the Battle of Leyte. Being tied to a single location made the Third Fleet vulnerable, and between October and December, three aircraft carriers were sufficiently badly damaged by kamikaze attacks to have to return to shipyards for repairs. McCain instituted new tactics to deal with them.[90] McCain continued to press for more fighters on his carriers, recommending on 20 November that the Helldivers be replaced with fighters. On 23 December, King announced that for the next cycle of operations, the Essex-class carriers would have 72 fighters, 15 dive bombers and 15 torpedo planes.[91]

While conducting operations off the Philippines on 17 December, McCain participated in Halsey's decision to keep the combined naval task force on station rather than avoid a major storm, Typhoon Cobra (later known also as "Halsey's Typhoon"), which was approaching the area. The storm sank three destroyers and inflicted heavy damage on many other ships. Some 800 men were lost, in addition to 186 aircraft. A Navy court of inquiry found that Halsey committed "errors of judgment" in sailing into the typhoon, but did not recommend sanction.[92]

On 8 and 9 January, McCain conducted air strikes against targets in Formosa and the Ryukyus. Task Force 38 then sailed through the Luzon Strait and raided the South China Sea. [93] A series of air strikes against targets in French Indochina saw Task Force 38 sink 15 warships and 29 merchant ships, twelve of which were oil tankers.[94] Spruance relieved Halsey and McCain was relieved by Mitscher on 26 January 1945, and Task Force 38 became Task Force 58 once more.[95]

Between 30 October 1944 and 26 January 1945, Task Force 38 had destroyed or damaged 101 Japanese warships and 298 merchant ships; its aircraft had shot down 357 Japanese aircraft over targets and 107 in the air over the task force; its anti-aircraft guns had accounted for 21 more, and 1,172 were destroyed on the ground. On the other side of the ledger, Task Force 38 had lost 203 aircraft, 155 pilots and 96 aircrew during operations, and 180 aircraft, 43 pilots and 9 aircrew in accidents.[95] McCain was awarded a Gold Star to his Distinguished Service Medal on 23 March 1945, for his "brilliant tactical control" of the fast carrier forces during operations in the Philippines and South China Sea from September 1944 to January 1945.[96][97]

After a period of leave in the United States, McCain reported back to Pearl Harbor on 1 April 1945. On 17 May, he hoisted his flag on the aircraft carrier USS Shangri-La at Ulithi. He relieved Mitscher on 28 May, and resumed command of Task Force 38.[98] On 4 June, Task Force 38 ran into a typhoon again after Halsey and McCain ignored advice from their task group commanders. No ships sank, but six men died and 36 ships were damaged, including the cruiser USS Pittsburgh, which lost its bow. The court of inquiry recommended that consideration be given to relieving Halsey and McCain of their commands.[99][100][101]

The new Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal was in favor of retiring Halsey. King agreed, but felt that since Halsey was a popular hero, his relief would make the Navy look bad. McCain was more vulnerable, and Nimitz decided to replace him.[99][100][101] On 15 July, McCain was informed that he would be handing over command of Task Force 38 to Towers on 1 September 1945 and become the deputy head of the Veterans Administration under General Omar Bradley.[102]

McCain remained in command of Task Force 38 through July, as Task Force 38 conducted raids on the home islands of Japan. McCain had doubts about the wisdom of conducting attacks on warships and shipping in Kure and the Seto Inland Sea, believing that attacks on airfields and aircraft factories were a better use of his resources, but he complied with Nimitz's orders.[103]

Death

[edit]

By war's end in August 1945, the stress of combat operations, lifelong anxiety, and probable heart disease had taken its toll.[104] McCain requested home leave to recuperate, but Halsey insisted that he be present at the Japanese surrender ceremony in Tokyo Bay on 2 September.[100]

Departing immediately after the ceremony, McCain arrived home in Coronado, California, on 5 September. In the middle of a welcome-home party the following afternoon, he told his wife that he did not feel well. At 17:10, he died of a heart attack. He was 61 years old.[105][100][106] His death was front-page news across the United States.[106][107] He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.[108] His honorary pall bearers were General Alexander Vandegrift, Vice Admirals Russell Willson, Leigh Noyes and Ferdinand Reichmuth, and Rear Admirals George S. Bryan and Matthias Gardner.[109]

Short in stature and of rather thin frame, McCain was gruff and profane; he liked to drink and gamble. He showed courage and was regarded as a natural, inspirational leader. In the words of one biographical profile, McCain "preferred contentious conflict to cozy compromise."[110]

Posthumous honors

[edit]In 1949, McCain was posthumously promoted to admiral by a resolution of Congress. This followed a recommendation of Secretary of the Navy Francis P. Matthews, who said that McCain's combat commendations would have earned him the promotion had he not died so soon after the war.[111] The date of rank was 6 September 1945, the day he died.[109] When his son later achieved this rank, they became the first father-and-son pair to do so.[112]

There were other posthumous honors. In December 1945, King George VI made McCain an honorary knight commander of the Order of the British Empire. An investiture ceremony was held on board the cruiser HMS Sheffield (anchored in Long Beach harbor) in July 1948.[113] In April 1946, McCain was awarded a second gold star to his Distinguished Service Medal for his service in command of Task Force 38 from 28 May to 1 September 1945. His citation read:

Combining brilliant tactics with effective measures to counter the enemy's fanatical aerial onslaughts, he hurled the might of his aircraft against the remnants of the much-vaunted Japanese Navy to destroy or cripple the every remaining major hostile ship by 28 July. An inspiring and fearless leader, Vice Admiral McCain maintained a high standard of fighting efficiency in his gallant force while pressing home devastating attacks which shattered the enemy's last vital defensive hope and rendered him unable to protect his shipping even in waters off the mainland of Japan.[113]

McCain Field, the operations center at Naval Air Station Meridian, Mississippi, was named in his honor.[110] The observatory building at the University of Mississippi was renamed McCain Hall on 7 October 1947. It housed the university's Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) unit until 1989. It has since been renamed Barnard Observatory, but the new Naval ROTC spaces, in another building, were named the McCain Quarterdeck in April 2003.[114]

The guided-missile destroyer USS John S. McCain (DL-3) (in service from 1953 to 1978) was named after him,[115][116] and the destroyer USS John S. McCain (DDG-56) (commissioned in 1994 and still in service as of 2024[update]) was named for him, his son, Admiral John S. McCain Jr., and, as of a rededication ceremony 11 July 2018, his grandson John S. McCain III.[112][117][118]

Dates of rank

[edit]- United States Naval Academy midshipman – 25 September 1902

| Ensign | Lieutenant (junior grade) | Lieutenant | Lieutenant Commander | Commander | Captain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-1 | O-2 | O-3 | O-4 | O-5 | O-6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 18 March 1908 | 13 February 1911 | 1 July 1912 | 22 September 1917 | 28 May 1918 | 30 June 1931 |

| Rear Admiral | Vice Admiral | Admiral |

|---|---|---|

| O-8 | O-9 | O-10 |

|

|

|

| 23 January 1941 | 28 July 1943 | 6 September 1945 |

Notes

[edit]- ^ McCain & Salter 1999, p. 21.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Trimble 2019, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b McCain & Salter 1999, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Trimble 2019, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Trimble 2019, pp. 6–8.

- ^ a b Gilbert 2006, p. 11.

- ^ Trimble 2019, p. 9.

- ^ Trimble 2019, pp. 9–10.

- ^ a b c d Reynolds 2002, p. 206.

- ^ a b Trimble 2019, p. 11.

- ^ a b Gilbert 2006, p. 14.

- ^ Trimble 2019, p. 12.

- ^ a b Gilbert 2006, pp. 15–16.

- ^ a b Trimble 2019, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 18–21.

- ^ Trimble 2019, pp. 13–14.

- ^ McCain 1923, pp. 19–37.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, David D. (12 October 2008). "Writing Memoir, McCain Found a Narrative for Life". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 October 2008.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 34–36.

- ^ Trimble 2019, pp. 14–16.

- ^ McCain 1924, pp. 417–423.

- ^ a b Trimble 2019, pp. 16–19.

- ^ McCain 1925, pp. 737–745.

- ^ a b c d Trimble 2019, pp. 20–24.

- ^ a b Trimble 2019, p. 27.

- ^ McCain, J. S. (1929). Causes of the Spanish American War, and the Naval and Combined Operations in the Atlantic, Including the Transfer of the Oregon (Thesis). U.S. Naval War College. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ McCain, J. S. (1929). Foreign Policies of the United States (Thesis). U.S. Naval War College. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 32–233.

- ^ a b c Trimble 2019, pp. 28–30.

- ^ a b c Gilbert 2006, pp. 40–43.

- ^ Trimble 2019, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b Trimble 2019, pp. 32–39.

- ^ a b Gilbert 2006, pp. 47–51.

- ^ Trimble 2019, p. 42.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Trimble 2019, p. 41.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b Trimble 2019, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 54–57.

- ^ Trimble 2019, pp. 43–46.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 60–64.

- ^ "H-008-3: Torpedo Versus Torpedo". Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 16 October 2024.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 64–68.

- ^ Boatner 1996, p. 106.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 75–79.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Trimble 2019, p. 66.

- ^ Trimble 2019, pp. 79–81.

- ^ a b Trimble 2019, p. 81.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Trimble 2019, pp. 83–85.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 92–94.

- ^ Trimble 2019, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Trimble 2019, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Reynolds 2013, pp. 40–44.

- ^ Trimble 2019, pp. 97–99.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, p. 96.

- ^ "Army & Navy – NAVY: Battle Lost". Time. 28 September 1942. Retrieved 12 June 2024.

- ^ "Letters". Time. 12 October 1942. Retrieved 13 June 2024.

- ^ Trimble 2019, p. 106.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Trimble 2019, pp. 108–110.

- ^ a b Furer 1959, p. 371.

- ^ Trimble 2019, p. 110.

- ^ a b Trimble 2019, p. 111.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 109–111.

- ^ Trimble 2019, p. 115.

- ^ Reynolds 2013, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Trimble 2019, pp. 130–133.

- ^ a b Gilbert 2006, pp. 121–126.

- ^ a b Trimble 2019, pp. 145–151.

- ^ a b Gilbert 2006, pp. 130–137.

- ^ a b Trimble 2019, pp. 153–157.

- ^ Morison 1958, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 137–140.

- ^ Trimble 2019, pp. 157–162.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 143–146.

- ^ Trimble 2019, pp. 167–170.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 146–149.

- ^ Trimble 2019, pp. 170–173.

- ^ a b Gilbert 2006, pp. 150–153.

- ^ Trimble 2019, pp. 175–173.

- ^ Trimble 2019, pp. 175–184.

- ^ Boatner 1996, p. 351.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 159–165.

- ^ Trimble 2019, p. 198.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 171–173.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 175–179.

- ^ Morison 1959, p. 169.

- ^ a b Gilbert 2006, p. 180.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, p. 182.

- ^ Trimble 2019, p. 242.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, p. 183.

- ^ a b Gilbert 2006, pp. 186–189.

- ^ a b c d Drury & Clavin 2006, p. 284.

- ^ a b Morison 1960, p. 308.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 192–193.

- ^ Trimble 2019, pp. 216–217.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 219–221.

- ^ a b "McCain dies suddenly at his home". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. 7 September 1945. p. 1.

- ^ "Admiral McCain dies". Milwaukee Sentinel. Associated Press. 7 September 1945. p. 1.

- ^ "Burial detail: McCain, John S". ANC Explorer. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ a b Gilbert 2006, pp. 223–224.

- ^ a b Leahy, Michael (31 August 2008). "A Turbulent Youth Under a Strong Father's Shadow". The Washington Post. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- ^ "M'Cain Promotion Passed". The New York Times. Associated Press. 28 August 1949.

- ^ a b Doornbos, Caitlin (12 July 2018). "McCain joins father and grandfather on ship's list of namesakes". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 18 July 2024.

- ^ a b Gilbert 2006, pp. 226–227.

- ^ Gilbert 2006, pp. 227–228.

- ^ "John S. McCain I (DL-3)". Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Naval Surface Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet > Ships > USS John S. McCain (DDG 56) > About". United States Navy. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ Blinder, Alan (30 May 2019). "What You Need to Know About the U.S.S. John S. McCain". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ Moritsugu, Ken (12 July 2018). "US Navy dedicates Japan-based destroyer to US Sen. McCain". AP News. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

References

[edit]- Boatner, Mark M. (1996). The Biographical Dictionary of World War II. Novato, California: Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-548-3. OCLC 60230621.

- Drury, Robert; Clavin, Tom (2006). Halsey's Typhoon: The True Story of a Fighting Admiral, an Epic Storm, and an Untold Rescue. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 0-87113-948-0. OCLC 71288798.

- Furer, Julius Augustus (1959). Administration of the Navy Department in World War II. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. pp. 217–222. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- Gilbert, Alton (2006). A Leader Born: The Life of Admiral John Sidney McCain, Pacific Carrier Commander. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Casemate. ISBN 1-932033-50-5. OCLC 71012417.

- McCain, John S. (January 1923). "A Personnel Survey". U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings. Vol. 49. pp. 19–37. ISSN 0041-798X. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- McCain, John S. (March 1924). "The Staff Equalization Bill". U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings. Vol. 50. pp. 417–423. ISSN 0041-798X. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- McCain, John S. (May 1925). "Service since Graduation vs. Age in Grade Retirement". U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings. Vol. 51. pp. 737–745. ISSN 0041-798X. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- McCain, John S. III; Salter, Mark (1999). Faith of My Fathers. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-375-50191-6. OCLC 40776751.

- Morison, Samuel E. (1958). Leyte, June 1944 – January 1945. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. XII. Boston: Little & Brown. OCLC 1035611842.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1959). The Liberation of the Philippines: Luzon, Mindanao, the Visayas, 1944–1945. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. XIII. Boston: Little & Brown. OCLC 7649371.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1960). Victory in the Pacific 1945. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. XIV. Boston: Little & Brown. OCLC 7649498.

- Reynolds, Clark G. (2002). Famous American Admirals. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-006-1. OCLC 47996093.

- Reynolds, Clark G. (2013). The Fast Carriers: The Forging of an Air Navy. Annapolis, Maryland: U.S. Naval Institute. ISBN 978-1-59114-722-0. OCLC 854618212.

- Trimble, William F. (2019). Admiral John S. McCain and the Triumph of Naval Air Power. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-68247-370-2. OCLC 1047650916.

- U.S. Navy Department (1947). Building the Navy's Bases in World War II, Volume II. History of the Bureau of Yards and Docks and the Civil Engineer Corps 1940–1946. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 1023942.

- 1884 births

- 1945 deaths

- American people of Scotch-Irish descent

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

- Honorary Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire

- McCain family

- Military personnel from Mississippi

- Naval War College alumni

- People from Carroll County, Mississippi

- Recipients of the Navy Cross (United States)

- Recipients of the Navy Distinguished Service Medal

- Recipients of the Order of the Sun of Peru

- United States Naval Academy alumni

- United States Navy admirals

- United States Navy personnel of World War I

- United States Navy World War II admirals

- University of Mississippi alumni

- United States Naval Aviators

- Phi Delta Theta members